Introduction: Curiosity, hedonism and Polite Society

How far will you go to appease your hedonistic desires? What if it defies the laws of Polite Society? Yorgos Lanthimos’s cinematic exploration of human nature in his film Poor Things (2003) introduces you to this concept. It is imperative for one who wishes to abide by society’s rules not to challenge its ways. Despite this, humans are naturally curious and have a hidden desire to know and to become more than the status quo. Audiences are rarely thrust into media that embody human curiosity and the innovation that follows. In Poor Things (2023), Lanthimos invites his audience to see the embodiment of human curiosity, created by a man driven by innovation, who is then exposed to a world obsessed with power and control. Lanthimos’s invitation encourages the audience to think about the power of curiosity in a world obsessed with suppressing feminine agency in the guise of Polite Society, showing the world through the eyes of a woman born a woman but raised to become human first.

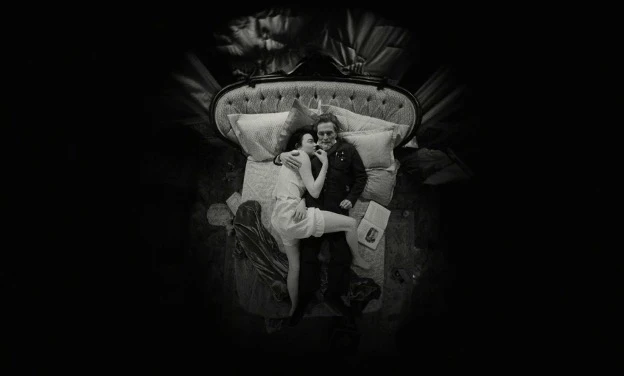

Emma Stone in Poor Things (2023), directed by Yorgos Lanthimos. Cinematography by Robbie Ryan. © Searchlight Pictures. Image courtesy of FILMGRAB.

Hedonistic desire, plot and the rules of Polite Society

What can we say about Poor Things that has not been said before? Poor Things is a surrealist black comedy with elements of body horror that challenges the notion of a human’s hedonistic desire for freedom in a world full of repressive control. We follow Dr Godwin Baxter and his ‘mentally challenged’ daughter, Bella Baxter, as the former records the growth and development of his child, later revealed to be an experiment on the connection between the body and the mind; the brain of a live infant implanted into the body of her deceased mother. In her journey to discovery, Bella Baxter joins morally corrupt lawyer Duncan Wedderburn on a whirlwind adventure around the world. Together, they gratify their hedonistic desires, indulging in all the sex, cuisine and culture money could buy, that is, until Bella discovers empathy and throws all of Duncan Wedderburn’s money away. Homeless and penniless, Bella Baxter seeks work as a sex worker, which angers Duncan Wedderburn, as, unlike their previous indulgent, promiscuous lifestyle, the idea of becoming a sexual servant to others to generate income is against the rules of polite society. It is a hypocrisy that is so satisfying to watch, especially in the downfall of those obsessed with polite society’s restrictive regimes.

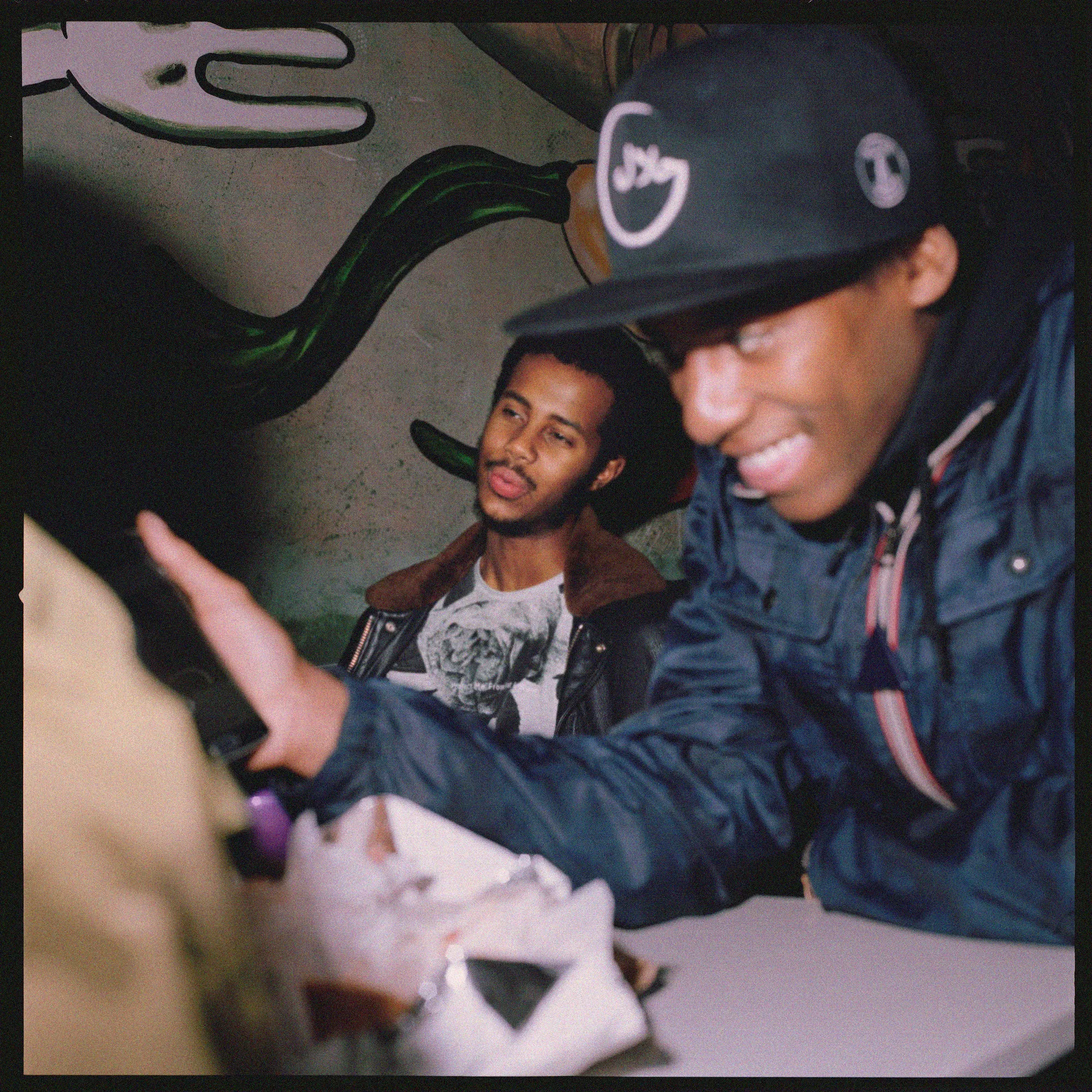

Emma Stone and Mark Ruffalo in Poor Things (2023), directed by Yorgos Lanthimos. Cinematography by Robbie Ryan. © Searchlight Pictures. Image courtesy of FILMGRAB.

Even when surrounded by the restrictive regime of Polite Society, none can contain the intensity of human curiosity and one’s desire to experience life and all of its indulgences. The freedom of experience is often granted to those who hold the most power. In patriarchal societies, a woman’s role is often passive, supporting the active man. Her agency is often controlled by the man, in the guise of helping her in her role within polite society. As Agency and Power are interconnected, a woman’s controlled freedom aligns with the maintenance of a man’s power. However, power in itself is not a repressive force that weighs on society, but rather a means to empower those to believe they have agency. We see this in Bella Baxter’s world, as we follow her experience through childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, being raised not as a woman but as a human being. An adult with the brain of a baby is an oddity in itself, but a woman possessing independent thoughts uninfluenced by the norms of polite society?

Emma Stone and Willem Dafoe in Poor Things (2023), directed by Yorgos Lanthimos. Cinematography by Robbie Ryan. © Searchlight Pictures. Image courtesy of FILMGRAB.

Body, autonomy and feminine agency

To understand Bella Baxter, one must consider what society did to her ‘mother’, Victoria Blessington. We see little of her backstory, but we see how, even in death, she is denied the human right to decency. As she is mutilated and used as Dr Godwin Baxter’s experiment, her dignity and identity as a woman are stripped away in the name of scientific discovery. Victoria has no freedom or agency to decide what she does with her body, which contrasts with Bella’s approach to her bodily autonomy, which she explores freely without considering the consequences. Emma Stone reflects this in an interview with The New York Daily News, “I think just in general the kind of societal things you grow up with around judgment of your body, judgment of other people, shame and all kinds of aspects of yourself. Restarting from scratch, that was a very inspiring part of Bella and a difficult thing to sort of strip away, but also extremely freeing.” Victoria never chooses to become a mother and dies before experiencing maternity. At the same time, Bella lives freely without the expectation of performance as a woman, having agency to explore the world and enrich herself sexually, intellectually and spiritually. In the words of Simone de Beauvoir, “One is not born a woman, but rather, becomes one.” Unlike Victoria, who experiences the nurture it takes to become a proper woman of Polite Society, Bella’s experience is the product of humanist intellectualism, which propels her to achieve a peak sense of feminine agency, one where she participates in society and contributes through her own unique skillset as a person rather than a woman, a wife, and/or a mother.

Emma Stone and Willem Dafoe in Poor Things (2023), directed by Yorgos Lanthimos. Cinematography by Robbie Ryan. © Searchlight Pictures. Image courtesy of FILMGRAB.

The men around Bella: power, control and the 'Born Sexy Yesterday' trope

However, in the case of Bella Baxter, one must note the effects of human nature and the men who surround her in her discovery of true feminine agency. Lanthimos introduces us to four men who serve as different roles in a woman’s life: Dr Godwin Baxter as the Father, Max McCandles as the Caretaker, Duncan Wedderburn as the Lover and Alfie Blessington as the Husband. All the men in Bella’s life are obsessed with power and control, from Dr Godwin’s obsession of keeping her hidden so as not to expose her to the cruelties of polite society, to Max McCandles’ obsession with maintaining her honour and innocence, to Duncan Wedderburn’s obsession with controlling her as his personal sexual object and Alfie Blessington’s obsession with retaining Bella as his property, much like how Victoria Blessington used to be. Women are often dehumanized within their role in society, as their performative role relies on being the supporting cast rather than the main lead.

Gender norms expect women to be passive, submissive and lacking in self-determination and sexual autonomy. Even as she journeys toward feminine autonomy, Bella is taken advantage of by the men around her for her naivete. She is quite literally a child stuck in an adult’s body, yet embodies the cinematic trope coined by Pop Culture Detective: Born Sexy Yesterday. Women who are deemed noteworthy must be intriguing spectacles but also possess traits that appease the male gaze. The appeal of Bella is that she makes the men around her feel powerful; her naivety appeals to a man’s desire for male superiority, which in turn becomes the cause of their downfall. Dr Godwin loses his daughter to her desire for freedom, Duncan Wedderburn drives himself to madness from his failure to conquer his emotionally stunted conquest, and Bella turns Alfie Blessington into her pet as revenge for holding her hostage. Only Max, who supports Bella’s acceptance of her feminine agency, wins at the end, showing that the solution was not to obsess over power but to appreciate the agency that power brings.

Emma Stone and Mark Ruffalo in Poor Things (2023), directed by Yorgos Lanthimos. Cinematography by Robbie Ryan. © Searchlight Pictures. Image courtesy of FILMGRAB.

Sexual agency, work and liberation

As Bella takes control of her own destiny, she reclaims the power she lost both as Victoria Blessington and Bella Baxter by becoming her own person in her pursuit of intellectualism. In her stint as a sex worker, she learns the strategic way women acquire power, using her sexuality to fund her pursuit of academia. Researchers suggest that sexual agency promotes and encourages liberation from external restrictions and fosters the exercise of free will and personal responsibility for one’s own behaviour. Bella sees her sex work as a means to encourage her journey to liberation, philosophically and literally, as it aids in her gaining freedom from the clutches of Duncan Wedderburn. Her return and subsequent discovery of her true origins may have led to a different outcome had she not experienced what she did. Bella grows as a person through her experiences, becoming more forgiving and understanding thanks to the freedom to explore the new world, a liberty not traditionally afforded to women in a patriarchal society. Through Bella, we learn that there is an emptiness to conformity and control, and true contentment lies in one’s own sense of discovery.

Emma plays a similar role in Bugonia, where her agency and identity are shaped by the ideological beliefs of a male conspiracy theorist — you can read the whole piece here: ‘Bugonia (2025): Corporations, Conspiracy Culture and the Chaos of Searching for Meaning’.

Emma Stone in Poor Things (2023), directed by Yorgos Lanthimos. Cinematography by Robbie Ryan. © Searchlight Pictures. Image courtesy of FILMGRAB.

Conclusion: freedom, risk and the 'Poor Things' among us

Is Poor Things a modern, feminist, cinematic masterpiece? Absolutely not. But despite its flaws, audiences can explore captivity vs. freedom, nature vs. nurture, and the effects of rigid social standards on those not given the privilege of benefiting from them. Through Bella Baxter, we explore the true meaning of discovering freedom and feminine agency by considering aspects of human nature and its impact on society as a whole. Yorgos Lanthimos guides his audience on a fantastical journey of philosophical discovery, encouraging you to interpret Bella’s pilgrimage through a humanistic lens. By approaching freedom through a humanist lens, the audience can see the effects of Power and Humanity’s obsession with power on the most vulnerable people, those who are naive and easy to take advantage of. But at the same time, you are the product of your experiences, and you will never become truly free if you deprive yourself of life itself. Poor Things traces a journey of self-discovery, showing that the Poor Things in question are often those afraid to take risks.

Works Cited

De Beauvoir, S., & Parshley, H. M. (1949). The second sex.

Pop Culture Detective. (2017, April 27). Born sexy yesterday [Video]. YouTube.

Wu, A. (2024, January 23). Poor Things: A cinematic masterpiece or a work of horror? The Justice.